For Catholics, November is a month of remembrance. We become mindful of many things we would prefer to forget – death and judgment, heaven and hell.

“Memory” in the Jewish, Catholic, and Orthodox traditions is not mainly a matter of looking backwards, but of becoming more mindfully present. Through holy rituals, we “remember” saving events such as the Passover in Egypt, the birth of Jesus, or his death and resurrection – in a way allows us here today to participate and become true sharers in those saving events. They become here and now for us. We also “remember” what is yet to come, the fullness of life in the Kingdom of God. We glimpse the goodness of the Lord in a foretaste and anticipation of more to come.

November begins with the twin celebrations of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day – reminding us that the love of Jesus connects all the members of the human family, even those beyond the grave. In the very flesh and blood of the risen Body of Christ, we are truly united to those who have gone before us. We are never alone. Our deepest longings are never in vain. We are reminded not to get stuck in this fallen world that is quickly passing away.

All around us (at least here in the Northern Hemisphere) nature enters its annual cycle of death and decay. So swiftly does the dazzling and majestic fruitfulness of fall plunge into darkness and decay – particularly for those of us in the upper Midwest!

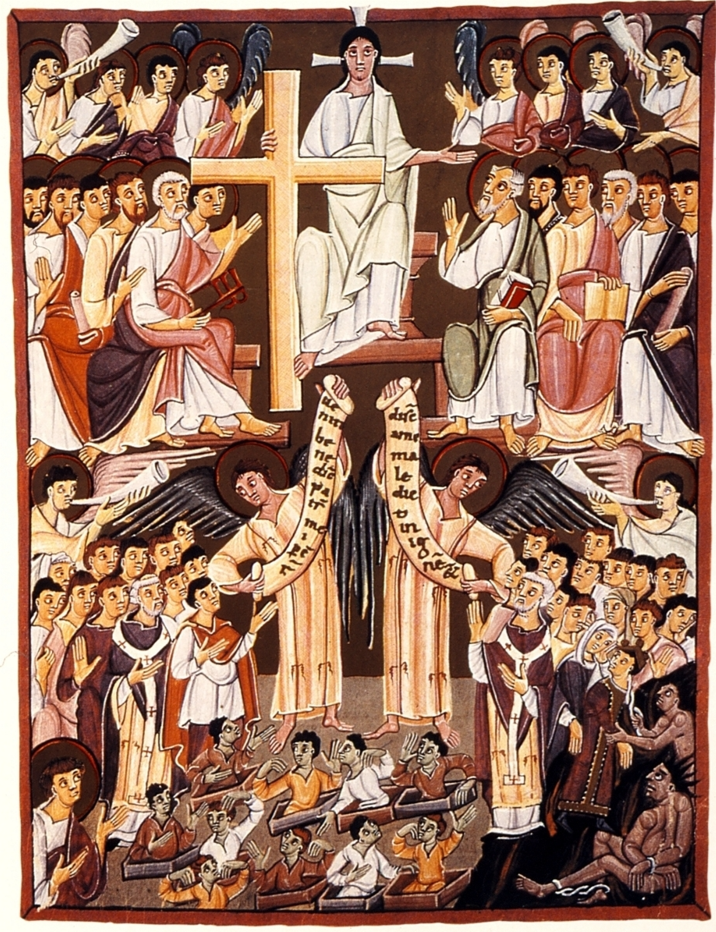

There is a marvelous medieval hymn traditionally sung during this month of remembering death and the Final Judgment: the Dies Irae. Amidst decades of what Bishop Robert Barron has often described as “Beige Catholicism,” this hymn has been all but forgotten. What is more, those few who remember it tend to be drawn to it for all the wrong reasons: fear-mongering, shaming, or scrupulosity. It doesn’t help that there are bad translations that reflect the shame of the translator more than the actual text. Indeed, the English translation provided in the video linked above describes “universal dread” and a “severe” Judge with “searching eyes.” None of those words are there in the original Latin poetry!

The Dies Irae has captivated human imagination for centuries. In 2014, Thomas Allen of the CBC (Canadian Broadcast Company) offered a playful and fascinating exposition on the influence of this hymn upon musical history.

Yes, the hymn is haunting and disruptive – especially to privileged Americans who would prefer to live comfortable lives and somehow stay young and powerful forever. But it is ultimately an invitation to trust Jesus and step into real Hope.

The world we live in, insofar as it was created by God, is good and beautiful. He entrusted it to us humans as the stewards. We failed in our stewardship. The world we live in, through the devil’s envy, malice, and seduction, is now enemy-occupied territory. Jesus describes the devil as “the ruler of this world” (John 12:31). This world and all the things in it are passing away (1 John 2:17).

The first verse of the Dies Irae reminds us that the “Day of Wrath” will dissolve this world in ashes. However, it goes on to describe the victory of Jesus on the Cross, and the invitation to humble ourselves before him as we receive the redemption that he freely gives. Neither our own merits nor any power of this world will save us on that day. We place our trust in Jesus alone.

“That Day” is also described as lacrimosa dies illa (“That Day of weeping”). We can see why this hymn has been buried in the West during my half century of human existence. We live in a culture that has forgotten how to grieve. And we definitely live in a culture that struggles to engage in real repair when harm has happened. “That Day” of Jesus’ coming will bring both. It is not merely a Day of Judgment; it is a Day that brings full Justice and definitive resurrection and renewal – which is only possible with the fulness of Love and Truth that Jesus will bring. Jesus will definitively heal our shame, if we will allow it.

I’ve developed a keen radar for shame. For several years now, I’ve been contending with my own shame (as well as the shame of others who harmed me in my life – shame that doesn’t belong to me). I’ve learned, at least some of the time, to stand calmly in the face of shame – not to run away, nor to power up, nor to freeze, but to draw closer with curiosity and kindness.

I’ve been learning from Jesus in the Gospels. He frequently pursues those who are feeling shame – when he calls Matthew the tax collector (Matthew 9:9), when he tells the woman caught in adultery “I don’t condemn you” (John 10:11), when he awakens the thirst of the Samaritan woman at the well (John 2), and in his various encounters with Peter. When Peter denies Jesus (as predicted), Jesus turns to look at Peter (Luke 22:61) – not with accusation, but with love and truth. Peter goes out and weeps bitterly. He sees an almost unbearable gaze of kindness – far more painful and more helpful than any accusation or name calling. Peter suffers again after the resurrection, when Jesus awaits him on the seashore, having already lit a charcoal fire (John 21:9-19). He reminds Peter of his threefold denial, not to add to Peter’s shame, but to bring that shame into the light and transform it.

These encounters with the merciful and truth-telling love of Jesus help me imagine what Judgment Day will be like. When I hear the chanting in the Dies Irae describing the “Day of Wrath” or “That Day of Weeping,” I imagine him gazing with love at each of these women and men in the Gospel, seeing right through them, accepting them, choosing them, and inviting them to total conversion. The kindness of Jesus always puts love and truth-telling together. Kindness heals shame, through a gentle yet utterly necessary unveiling of the full truth. That is what “apocalypse” literally means – “uncovering” or “unveiling.”

Shame is a master of disguises. It shows up in outbursts of rage, in ghosting other people, in “cancel culture,” in witty-but-cruel name calling, in self-loathing, or in self-destructive behaviors. Where there’s contempt, there’s probably shame. Where there’s vagueness, there’s probably shame. Where there’s all-or-nothing language, there’s probably shame. I’ve learned to detect the lurking presence of shame, and to draw closer to it, while respecting the sacredness of others’ freedom. This kind and curious pursuit is not what people expect! I love those moments when it becomes possible to tell the fuller truth with kindness – not to paper over, not to humiliate or condemn, but to be with each other in love and respect while acknowledging all the particulars.

This definitive repairing through the kindness and justice of God is exactly what the Dies Irae is about. Jesus will assemble the nations. Death will stand in astonishment as all the tombs are opened, and all our bodies raised (John 5:25-29). The victory wrought by Jesus on the Cross – overthrowing the cruel empire of sin and death – will be fully unveiled. So will all of our thoughts, words, actions, and omissions. The stories of each and all will be told in their full and unedited versions. In the words of the Dies Irae, “The written book shall be brought forth, in which all is contained, from which the world shall be judged.” No doubt, “My face will blush with guilt” – just like Peter or Matthew or the Samaritan woman. In my fear and shame, I may dread that “the day” will be like a blazing oven that burns up everything (Malachi 3:19) But if my trust is in the victory of Jesus, I will experience “the sun of justice with its healing rays” (Malachi 3:20). There is no other way.

We can conclude with the beautiful words of Pope Benedict XVI in his 2007 encyclical letter on Hope. He describes this encounter with the fire of Jesus’ love, whether on the Day of Judgment, or as a purgatorial experience following my own death. He comments on the apostle Paul’s reflections in 1 Corinthains 3, which describe some of us being saved, but “as through fire.” As Benedict explains, “the fire which both burns and saves is Christ himself, the Judge and Savior. The encounter with him is the decisive act of judgment. Before his gaze all falsehood melts away. This encounter with Him, as it burns us, transforms and frees us, allowing us to become truly ourselves. All that we build during our lives can prove to be mere straw … and it collapses. Yet in the pain of this encounter, when the impurity and sickness of our lives become evident to us, there lies salvation. His gaze, the touch of His heart heals us through an undeniably painful transformation ‘as through fire’. But it is a blessed pain, in which the holy power of his love sears through us like a flame, enabling us to become totally ourselves and thus totally of God” (Spe Salvi n. 47).

Without the Day of Judgment, we cannot share fully in God’s holiness, nor be fully and authentically human. Only the truth-telling and merciful love of Jesus can bring full flourishing and righteousness. Therefore, we pray ancient Christian prayer: “Come, Lord Jesus!”